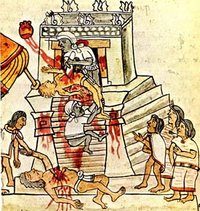

For millennia the practice of human sacrifice was widespread in Mesoamerican and South American cultures. It was a theme in the Olmec religion, which thrived between 1200 BC and 400 BC. Later the Inca and Maya also made human sacrifices, but the Aztecs practiced it on a particularly large scale.

For the reconsecration of Great Pyramid of Tenochtitlan in 1487, the Aztecs reported that they sacrificed about 84,400 prisoners over the course of four days, This would mean almost 15 per minute for 24 hours a day. Tenochtitlan itself had an estimated population of 80,000 to 120,000 in that time, with as many as 700,000 in the cities immediately surrounding Lake Texcoco. Since the Aztecs reported the number of sacrifices themselves, they could have inflated the number as a propaganda tool especially if, as reported, Ahuitzotl sacrificed them personally.

Aztec sacrifice

The Structure of Aztec Society

Class structure

The society traditionally was divided into two social classes; the macehualli (people) or peasantry and the pilli or nobility. Nobility was not originally hereditary, although the sons of pillis had access to better resources and education, so it was easier for them to become pillis. Eventually, this class system took on the aspects of a hereditary system. The Aztec military had an equivalent to military service with a core of professional warriors; only those that had taken prisoners could become full-time warriors, and eventually the honors and spoils of war would make them pillis. Once an Aztec warrior had captured 4 or 5 captives, he would be called tequiua and could attain a rank of Eagle or Jaguar knight, sometimes translated as "captain", eventually he could reach the rank of tlacateccatl or tlachochcalli. To be elected as tlatoani, one was required to have taken about 17 captives in war. When Aztec boys attained adult age, they stopped cutting their hair until they took their first captive; sometimes two or three youths united to get their first captive; then they would be called iyac. If after a certain time, usually three combats, they could not gain a captive, they became macehualli; their hair would still be quite long, indicating that they had not gotten a captive yet. That was rather shameful.

The abundance of tributes led to the emergence and rise of a third class that was not part of the traditional Aztec society: pochtecas or traders. Their activities were not only commercial: they also were an effective intelligence gathering force. They were scorned by the warriors - who nonetheless sent to them their spoils of war in exchange for blankets, feathers, slaves, and other presents.

In the later days of the empire, the concept of macehualli also had changed. Eduardo Noguera (Annals of Anthropology, UNAM, Vol. xi, 1974, p. 56) estimates only 20% of the population was dedicated to agriculture and food production. The chinampa system of food production was very efficient; it could provide food for about 190,000 people. Also, a significant amount of food was obtained by trade and tribute. The Aztec were not only conquering warriors, but also skilled artisans and aggressive traders. Eventually, most of the macehuallis were dedicated to arts and crafts. Their works were an important source of income for the city (Sanders, William T., Settlement Patterns in Central Mexico. Handbook of Middle American Indians, 1971, vol. 3, p. 3-44).

Excavations of some cities under Aztec rule show that a sizeable number of luxury items were produced in Tenochtitlan. More excavations are needed to show if this was true in other Aztec provinces, but if trade was as important as it seems, this could explain the rise of the Pochteca as a powerful class.

Aztec pyramid Cholula

Slavery

Slaves or tlacotin (distinct from war captives) also constituted an important class. This slavery was very different from what Europeans of the same period were to establish in their colonies, although it had much in common with the slaves of classical antiquity. (Sahagún doubts the appropriateness even of the term "slavery" for this Aztec institution.) First, slavery was personal, not hereditary: a slave's children were free. A slave could have possessions and even own other slaves. Slaves could buy their liberty, and slaves could be set free if they were able to show they had been mistreated or if they had children with or were married to their masters.

Typically, upon the death of the master, slaves who had performed outstanding services were freed. The rest of the slaves were passed on as part of an inheritance.

Another rather remarkable method for a slave to recover liberty was described by Manuel Orozco y Berra in La civilización azteca (1860): if, at the tianquiztli (marketplace; the word has survived into modern-day Spanish as "tianguis"), a slave could escape the vigilance of his or her master, run outside the walls of the market and step on a piece of human excrement, he could then present his case to the judges, who would free him. He or she would then be washed, provided with new clothes (so that he or she would not be wearing clothes belonging to the master), and declared free. Because, in stark contrast to the European colonies, a person could be declared a slave if he or she attempted to prevent the escape of a slave (unless that person were a relative of the master), others would not typically help the master in preventing the slave's escape.

Orozco y Berra also reports that a master could not sell a slave without the slave's consent, unless the slave had been classified as incorrigible by an authority. (Incorrigibility could be determined on the basis of repeated laziness, attempts to run away, or general bad conduct.) Incorrigible slaves were made to wear a wooden collar, affixed by rings at the back. The collar was not merely a symbol of bad conduct: it was designed to make it harder to run away through a crowd or through narrow spaces.

When buying a collared slave, one was informed of how many times that slave had been sold. A slave who was sold four times as incorrigible could be sold to be sacrificed; those slaves commanded a premium in price.

However, if a collared slave managed to present him- or herself in the royal palace or in a temple, he or she would regain liberty.

An Aztec could become a slave as a punishment. A murderer sentenced to death could instead, upon the request of the wife of his victim, be given to her as a slave. A father could sell his son into slavery if the son was declared incorrigible by an authority. Those who did not pay their debts could also be sold as slaves.

People could sell themselves as slaves. They could stay free long enough to enjoy the price of their liberty, about twenty blankets, usually enough for a year; after that time they went to their new master. Usually this was the destiny of gamblers and of old ahuini (courtesans or prostitutes).

Motolinía reports that some captives, future victims of sacrifice, were treated as slaves with all the rights of an Aztec slave until the time of their sacrifice, but it is not clear how they were kept from running away..

Aztec pyramid of the sun

Daily Life

Diet

The Aztec created artificial islands or chinampas on Lake Texcoco, on which they cultivated crops. The Aztec staple foods included maize, beans and squash. Chinampas were a very efficient system and could provide up to seven crops a year, on the basis of current chinampa yields, it has been estimated that 1 hectare of chinampa would feed 20 individuals, with about 9,000 hectares of chinampa, there was food for 180,000 people.

Much has been said about a lack of proteins in the Aztec diet, to support the arguments on the existence of cannibalism (M. Harner, Am. Ethnol. 4, 117 (1977)), but there is little evidence to support it: a combination of maize and beans provides the full quota of essential amino acids, so there is no need for animal proteins. The Aztecs had a great diversity of maize strains, with a wide range of amino acid content; also, they cultivated amaranth for its seeds, which have a high protein content.

They cultivated chia, also high in protein. More important is that they had a wider variety of foods. Chilis and tomatoes, prominent to this day, were cultivated. They harvested acocils, a small and abundant shrimp of Lake Texcoco, also spirulina algae, which was made into a sort of cake that was rich in flavonoids, and they ate insects, such as crickets (chapulines), maguey worms, ants, larvae, etc. Insects have a higher protein content than meat, and even now they are considered a delicacy in some parts of Mexico. Aztecs also had domestic animals, like turkey and some dog breeds that provided meat, although usually this was reserved for special occasions. Hunting was also another source of meat—deer, wild hogs, ducks etc.

A study by Montellano (Medicina, nutrición y salud aztecas, 1997) shows a mean life of 37 (±3) years for the population of Mesoamerica.

Aztecs also used maguey extensively; from it they obtained food, sugar (aguamiel–honey water), drink (pulque), and fibers for ropes and clothing. Use of cotton and jewelry were restricted to the elite. They also kept beehives and harvested honey. Cocoa grains were used as money but also to make a chocolate drink much like beer. Subjugated cities paid annual tribute in form of luxury goods like feathers and adorned suits.

After the Spanish conquest some foods were outlawed, particularly amaranth because of its central role in religious belief, and there was less diversity of food. This led to chronic malnutrition in the general population.

0 comments:

Post a Comment